China is a supply chain and manufacturing superpower — a key advantage for China and a vulnerability for America.

Supply chain security is just one of the many battlegrounds that will be played out in this decisive decade of rivalry between America and China. It will either confirm or upend America’s role as the world’s leading power.

This rivalry will not only circle the globe in search of critical minerals, but will extend from the oceans’ seabed to space as China is already both a maritime and space power, with great ambitions to be a superpower in both.

America is a software superpower, but hardware and software are both important for production is power, a skilled workforce is power, and both are built from the ground up.

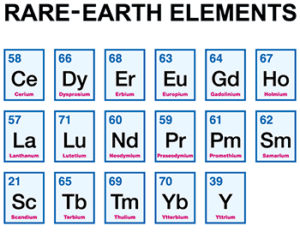

This brings us to rare earth elements — what the Japanese refer to as “industrial vitamins.”

America’s rare earths and tech metal supply chain fragility is both dangerous and puzzling. To a great degree, it could have been prevented with just a modicum of foresight.

America has one of the world’s greatest rare earths mine in Mountain Pass, California.

America has ample domestic natural resources, plus it borders commodity-rich Canada and South America.

So how did we ever become dependent on China for the supply of rare earths and rare metals critical to our technology and defense base?

In short, China’s massive advance over the past three decades to become a mining and refining superpower while Washington slept is an unforced error in our age of US-China rivalry.

The cause is not complex and can be traced to a rigid belief in the free market solving all strategic issues. Letting the S&P 500 run our international economic policy to optimize stock price led to shifting of our industrial base to China.

In a nutshell, we seem to have forgotten that America’s economic security, financial security, and national security are all one and the same.

A few highlights of this debacle include closing the US Bureau of Mines in 1996, allowing America’s only rare earths mine to go bankrupt, winding down our defense stockpile, and standing passively by as China became a global manufacturing superpower while locking up most of the production of the strategic metals in the world.

Daniel Yergin’s riveting tale of the major role oil played in the 20th century, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power traces the growing reliance on oil for both global commerce and war.

Oil not only powered economies, but it also played a pivotal role in the century’s statecraft from Winston Churchill’s decision to shift the Royal Navy from coal to oil in 1911, to the first Gulf War in 1991–1992 when America led a 35-country coalition to expel Iraq from Kuwait.

The following sentence in the book’s prologue sums up the world’s predicament today:

“As we look toward the 21st century, it is clear that mastery will certainly come as much from a computer chip as from a barrel of oil.”

But what’s behind the computer chip and technology that forms the backbone for so much that we take for granted in modern life? The answer is rare strategic metals and rare earths.

These natural resources are critical to economic growth and advancement of technology. They are also invisibly intertwined with national strategies, geopolitics, wealth, and power. The National Geographic magazine titled an article on these metals “The Secret Ingredients to Everything.”

What exactly are rare strategic metals and rare earths? They are neither precious metals like gold nor common metals like copper or lead.

Rather they are obscure rare metals like dysprosium, terbium, gallium, hafnium, indium, and rhenium that is in all sorts of products from cell phones to advanced weapons systems, aircraft engines, robots, and hybrid batteries.

The real value of rare earth elements, for example, is their unique electrical and magnetic properties that allow for miniaturization and much lighter, stronger, resilient, and efficient components. Rare earths are very difficult, time consuming, and environmentally problematic to extract from common ores and refine into oxides.

America is very dependent on imports of many of the ingredients that go into electric vehicles including the materials that make up the battery and the electric motor. There is a global race to control many of these technology metals and China is winning.

America dominated rare earths production at that time but over the past few decades, China has become the Saudi Arabia of rare earths. China’s low-cost labor and lax environmental standards allows it to produce up to 85% of world production of rare earth oxides. And as China becomes the center of the world’s ecosystem for electric vehicles, domestic demand for their production is rising.

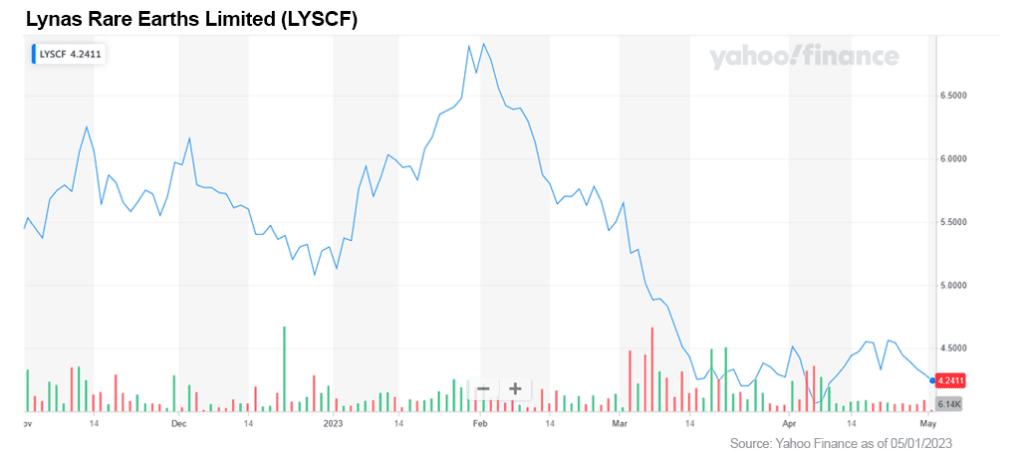

Rare earths expert Jack Lifton notes that the world needs seven more rare earth suppliers of the current size of Lynas (ASX: LYC / OTC US: LYSCF), the world’s #2 producer, over the coming years just to cover China’s increased domestic demand.

A F-35 fighter jet requires 920 pounds of rare metals and a Virginia class submarine 9,200 pounds, according to the Congressional Research Service. While in 1918, the British statesman Lord Curzon famously said that the Allied cause had “floated to victory upon a wave of oil” — in the 21st century, victory will depend on a river of rare earths and rare metals.

America’s dependency on China and other unstable sources of these minerals has led to an unfortunate window of strategic vulnerability.

Furthermore, China is doubling down on its commanding lead by having its state-sponsored firms gobble up reserves and mining assets all over the world — even in America’s neighbors, Canada, and Latin America.

To meet the expanding needs of a green economy, the US will need exponentially more supply than current levels as investment into electric vehicles, wind power and other renewable technologies climb through the 2020s.

For example, from 2022 through 2035, Adamas forecasts that global demand for permanent magnets will jump at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.6%, underpinned by double-digit growth from the electric vehicle and wind power sectors. Furthermore, China has more than 90% share of the global production of downstream rare earth products and technologies, including magnets.

There are some that say that in our global economy, this sort of dependency is no problem, let the market work its magic — all will be well. History tells a different story and China has wielded its leverage with ruthlessness a decade ago during a territorial dispute when China temporarily cut off exports of key critical metals vital to Japan’s technology economy. In just weeks, prices of many of these materials skyrocketed.

Here are some ways you as an investor could profit from America’s unfortunate situation.

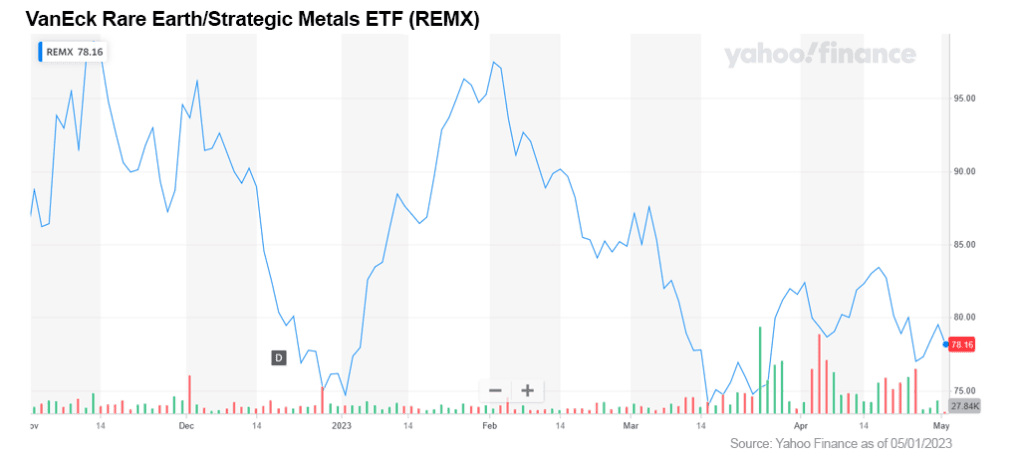

An easy way is through the strategic metals exchange-traded fund, VanEck Vectors Rare Earth/Strategic Metals ETF (NYSE: REMX). This is a basket of companies involved in strategic metals and rare earths with a fair amount of exposure to Chinese companies.

Another way is through an Australian company that has about a 14% global market share of rare earths; it’s called Lynas Corporation Limited (ASX: LYC / OTC US: LYSCF). Lynas has a processing facility in Malaysia and recently signed a preliminary agreement to do the same in Texas.

For more aggressive investors, there are also some smaller speculative companies that have a higher risk / reward profile. One approach is to back a company developing rare earth projects in North America.

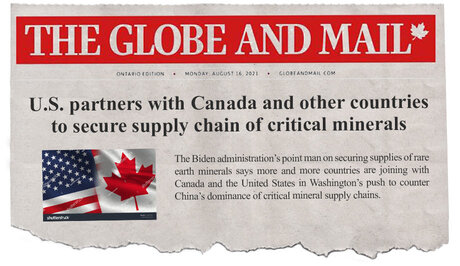

Canada is resource rich and a member of NATO so it’s naturally the closest political, economic, and geographical partner of the United States. All this makes Canada the ideal candidate for mining rare-earth elements for the United States' green tech and defense sectors.

The US Department of Defense has already had "preliminary discussions" with several Canadian mining companies working on rare-earth projects. These discussions are part of a broader strategy of the US and its allies to reduce their reliance on non-friendly regimes, including China. This is called "friendshoring," moving supply chains within the borders of democratic economies.

The result is an impending Canadian rare-earth industry renewal. Plus, the Canadian government has announced a $3.8-billion package in federal funds that would be used to boost the country's production of critical minerals. Rare-earth elements are on that list, of course.

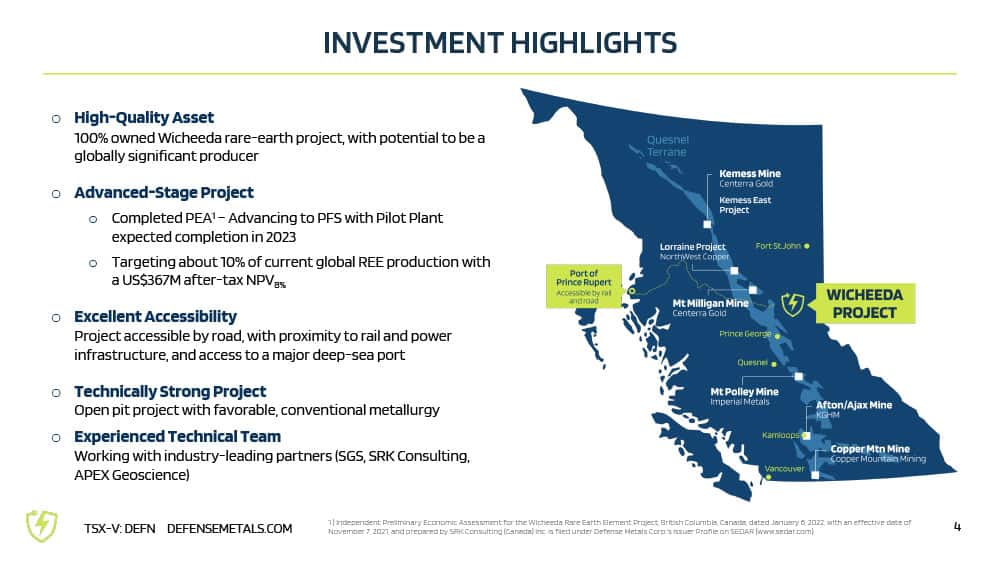

Just one of the companies seeking to end Western dependency on China is a Canadian resource company with the ambitious goal of providing 10% of the global supply of two vital rare earths is Defense Metals Corp. (OTCQB: DFMTF / TSX-V: DEFN / FSE: 35D).

Defense Metals is focused on two rare earths, neodymium and praseodymium, that are vital to the expansion of electric vehicles (EVs). This is because an electric vehicle (EV) uses 3kg–5kg worth of neodymium–iron–boron (“NdFeB”) magnets in standard drive train electric motors.

Global demand for EVs is expected to grow from 8 million in 2022 to over 40 million by (or before) 2030. This will require huge amounts of rare earths, most notably neodymium and praseodymium.

Rare earths expert Jack Lifton notes that China alone conservatively forecasts praseodymium-neodymium (NdPr) needs for just its own production of neodymium (NdFeB) permanent magnets as 78,000 tons per year by 2030.

The Pentagon, and by extension prime defense contractors, are also concerned by America’s heavy dependence on rare earths and many critical metals produced by China.

Magnet rare earths neodymium and praseodymium are just what Defense Metals intends to produce after further financing and other regulatory permits for their 100% owned Wicheeda Rare Earth Element Project. This project is spread over 4,244 hectares and located 80 km northeast of Prince George, British Columbia, Canada.

If they obtain production, Defense Metals targets to produce about 25,000 tons per year of rare earth oxides over a 16-year mine life, which would make the company a globally significant rare earths producer representing 10% of the current global production.

There are some other positive factors investors need to take into consideration.

First, Defense Metal’s Wicheeda Project has very good road access and is close to critical infrastructure, including rail and power about 80km from Prince George, British Columbia, and the project is accessible by road.

Second, it has reached a Mineral Exploration Agreement with the McLeod Lake Indian Band regarding its project that puts in place a framework for communication and cooperation going forward.

Third, Defense Metals can also add value as it tests an acid bake extraction process for rare earths that could lower capital and operating costs. This process is expected to increase the recovery rate for rare earths, compared to the alternative caustic cracking process.

Whether you take an ETF or stock approach, some exposure to rare earths and critical metals in your portfolio is a great hedge on US-China rivalry as well as an effective way to invest in clean energy.

Carl Delfeld, Contributor

for Investors News Service

P.S. To discover more opportunities in the hottest sectors in North America, sign up now to the Financial News Now newsletter to get the latest updates and investment ideas directly in your inbox!

DISCLAIMER: Investing in any securities is highly speculative. Please be sure to always do your own due diligence before making any investment decisions. Read our full disclaimer here.

Bloomberg, 2022, A news article describing the nature of supply chains disruptions in the base metal industry. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-06/white-hot-metal- market- cools-in-warning-for-global-economy.

Keith Bradsher, “Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan,” The New York Times, September 23, 2010. (https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/23/business/global/23rare.html)

Department of Defense, 2022, Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains. An action plan developed in response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017.

DeWit, A., 2021, Rikkyo Economic Review, Vol. 75, No. 1, July 2021, pp. 1 -32 1, The IEA’s Critical Minerals Report and its Implications for Japan.

Eckes, A. E. 1979, The United States and the Global Struggle for Minerals, University of Texas Press,

Offerman, E. (ed.). Chapter; A Historical Perspective of Critical Materials: 1939 to 2006 London: World

Leruth, L., Mazarei, A., Régibeau, P., Renneboog, L., 2022, Green Energy Depends on Critical Minerals. Who Controls the Supply Chains?